The Right to Rot: How Biomaterials Disrupt the Myth of Eternal Art

In the far corner of a gallery, under a bell jar, a work is quietly changing its mind. Yesterday it read as a crisp, pale object—almost industrial in its cleanliness. Today, a soft grey bloom creeps along its edge. Mycelium doesn’t “age” the way bronze does; it acts. It measures humidity, detects drafts, and responds to the salt in human breath. Nearby, a thin membrane catches the light like skin: bacterial cellulose, grown rather than fabricated, holding its own layered history—every ripple a trace of fermentation, every density shift a record of time spent alive. A little further on, an algae-based bioplastic form sits close to a radiator and subtly slumps, as if refusing the museum’s oldest demand: stay still, stay forever.

We’ve been trained to treat permanence as a virtue. The museum—white walls, controlled climate, dustless air—operates like a life-support system for objects. It lifts artworks out of the messy circulation of the world and seals them inside a fantasy of continuity. But biomaterials are uncooperative citizens of that fantasy. Mycelium, bacterial cellulose, algae bioplastics: these aren’t inert substances waiting to be shaped. They carry metabolism, moisture, and microbial alliances. They behave less like “materials” and more like collaborators—nonhuman subjects that negotiate, react, sometimes even resist. To work with them is to accept a basic shift in authorship: you don’t fully command the outcome; you set conditions and witness what follows.

This is where their politics begin—not with a green label, but with a refusal. Biomaterials insist on what we might call the right to rot. They drag decay out of the category of failure and return it to the realm of legitimacy. And once you accept that a work may be designed to disappear, the museum’s logic starts to wobble: if an artwork is destined to grow, soften, mould, dry, crack, or dissolve, how do we measure value? What happens to the idea of “collecting” when the object is less possession and more event?

One answer is uncomfortable: the myth of eternal art is not just an aesthetic preference. It is an industrial dream—an extension of a civilisation that believes it can freeze the world into assets, preserve prestige indefinitely, and postpone consequences with better storage and stronger packaging. Biomaterials puncture that dream, not with slogans, but with behaviour. They leak time back into the room.

Take bacterial cellulose in the Lapso–Celium series by Polybion and Natural Urbano: lighting objects that foreground growth rather than manufacture, where every surface bears the unrepeatable signature of fermentation—creases, gradients, thickness changes that no mould can truly standardise. The material doesn’t merely wear; it remembers. It turns the gallery into a living set of conditions, and the artwork into a negotiation with air, light, moisture—an ecology rather than a product.

Or consider BactoBerries by Debarati Das, which approaches material through intimacy rather than spectacle. It asks what “clean” might mean in the context of water scarcity and proposes a shift from sterilising the body to strengthening its own microbial ecosystem. Seeds, plant waste, and bio-based components become pods—objects that carry a quiet provocation: hygiene doesn’t have to be domination. Even here, in the private theatre of skin, the human is not alone; we are a habitat.

Mycelium, meanwhile, behaves like a curator with no interest in your schedule. It reorganises agricultural waste and fibres into new structures, but the “new” it produces is never the polished newness of industry. It comes with dirt-smell, uncertainty, and a slight insistence that your control is partial. You can design a form, yes—but you’re really designing a climate: warmth, humidity, nutrition, time. The mycelium replies, but it doesn’t obey. In that sense, it’s a material that trains humility.

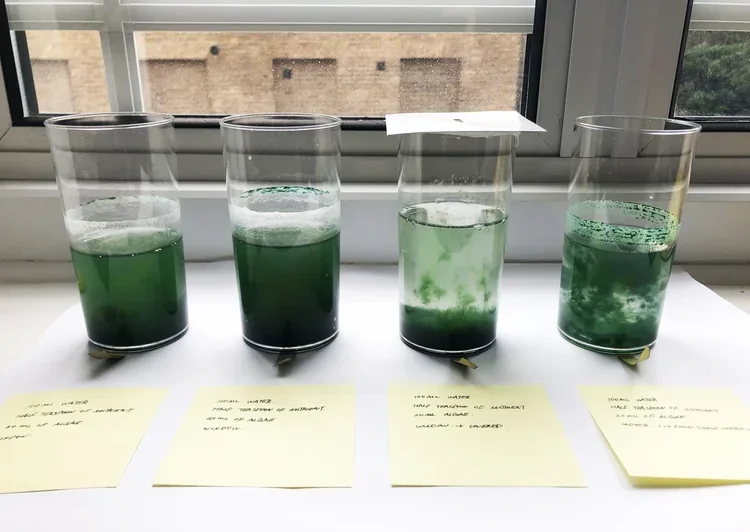

And then there is algae—especially when algae crosses from the food system into the material system. Hello! Algae by Zhenjing Lang reframes spirulina cultivation as a domestic, urban ritual. You don’t merely use algae; you watch it, feed it light, learn its moods. Nature ceases to be a distant landscape and becomes a relationship on your countertop. When algae becomes bioplastic, the critique sharpens. It looks like plastic, but refuses plastic’s most devastating promise: endurance without responsibility. It can deform, soften, break down—reminding us that what we’ve called “quality” is often just the violence of delayed decomposition.

This is exactly why the current design world’s obsession with biomaterials can feel so bitter. Too often, biomaterials are treated as a fashionable veneer: a little mycelium here, a little algae there, and suddenly a project claims moral exemption. Greenwashing thrives on gestures—on the consumption of “saving” as an aesthetic pose. We’re not always saving the planet; sometimes we’re simply monetising the feeling of being the kind of person who would.

The antidote is not purity. It’s honesty—and a willingness to let biomaterials do what they do best: disrupt the fantasy of permanence. Luffa Stoolita by Justin Wan’s team is compelling in precisely this way: using luffa fibres, coffee grounds, and clay-rich soil to produce a stool that doesn’t pretend to be immortal. Its strength is real, but so is its vulnerability. It carries an implicit message that industrial furniture has spent a century trying to erase: degradation is not a defect; it’s part of the contract.

Non-human centric thinking—symbiotic aesthetics, if you prefer—shouldn’t be a trendy frame pasted onto objects. It’s an ethic of relinquishing control. If we take biomaterials seriously as co-authors, we have to accept that we too will be changed: by the materials’ timelines, by their decay, by the fact that the artwork may refuse to remain what it was.

So we return to the hard question: if a work is designed to rot, what becomes of its value?

Maybe we need new verbs. Instead of asking how long a piece will last, we ask how it returns. Instead of worshipping the “forever object,” we learn to design dignified disappearance. In that shift, art ceases to function as a monument to industrial civilisation and instead participates in cycles: growth, use, breakdown, nourishment, reformation.

The final insight is blunt, almost earthy: matter has never belonged to us. “Eternity” is often just a technical method for hiding decay. “Progress” is frequently the power to postpone decomposition—and outsource it elsewhere. Biomaterials bring the outsourced half back into view. They invite art to stop performing immortality and start practising reciprocity.

Not everything needs to endure. Some things need to be composted.

Responsible Editor

Isabel Pavone