Synapses in the Weft: When Smart Textiles Start Sensing the World for Us

You walk into a room, and the first thing you notice isn’t the artwork—it’s the air. Not the temperature, exactly, but the way the air seems handled. Held in the folds. Released in slow, reluctant puffs. A textile hangs in the space like an animal that has learned to stay very still. Then someone shifts their weight. A heel taps. The cloth answers with a barely perceptible tightening along its edge, as if it’s listening with a body rather than ears. For centuries, fabric has been the quietest of materials: domestic, dutiful, built to absorb. It covers skin. It softens hard architecture. It holds stories the way a pillow holds the shape of a head that has just left it. Yet the newest wave of textile art refuses to remain a “surface.” It wants to be an organ. It wants feedback. It wants to act. The tapestry is no longer content to remember. It wants to respond.

I keep thinking about this shift—this move from static covering to interactive medium—through a few projects you’ve published on Art and Materials Lab, because they’re less interested in showing off “innovation” and more interested in what sensing does to our trust in touch.

Take Ievy Lin’s Unexpected yet nice touch. It doesn’t arrive waving the flag of technology. It arrives as a small, precise disturbance between what the eye believes and what the hand discovers. The work leans into that intimate moment of doubt—is this what I thought it was?—and makes the doubt linger. Colour becomes a misdirection. Finish becomes a trapdoor. The “nice touch” is nice because it is not fully obedient; it slips away from certainty.

That kind of sensory misalignment is exactly where smart textiles begin to feel inevitable. Because once fabric starts sensing, it doesn’t simply gain a new function; it re-orders the hierarchy of your senses. It asks you to renegotiate the old contract: you touch, it stays still; you look, it stays mute. What happens when the cloth answers back?

Jie Lin’s SensitiveMe pushes the question into the territory of mood—colour not as decoration but as a physiological lever. There’s a reason her research touches hospital palettes, those carefully controlled atmospheres where a shade can sedate or alarm. The textile here becomes a regulator: light and hue shifting like a nervous system trying to settle itself, or trying to settle you. You come to observe, and you realise—uncomfortably—that you’re being tuned.

Now imagine those instincts—the doubt in touch, the modulation of feeling—wired into matter that literally performs.

Shape-memory alloy (SMA) is the blunt instrument that makes poetry possible. It’s often introduced as a clever trick (“metal that remembers”), but in textile work, it behaves less like a trick and more like a muscle. Stitch it into cloth, and it stops being metal’s usual promise of rigidity. Under heat or electrical current, it tightens, flexes, and returns. The fabric gains posture. It can arch. It can brace itself. It can recoil like skin that has been startled.

A hanging textile with SMA doesn’t “move” so much as compose itself. It gathers into pleats the way a shoulder gathers into tension. It releases again with the tired grace of exhaling. And because the movement originates inside the structure, it doesn’t read as spectacle; it reads as a bodily reaction—private, involuntary, a little too close for comfort. Conductive polymer fibres take you further in. They aren’t muscles. They’re nervous. They sit inside the textile and register small pressures, the drag of a palm, the extra weight of humidity in the air. In some contexts, they can even pick up faint bodily signals—those quiet electrical fluctuations that leak through skin when we’re anxious or excited. Woven through cloth, these fibres turn fabric into a sensing field. Touch is no longer an event that ends at the fingertip. Touch becomes data. It becomes a trace that can be stored, replayed, and learned from.

And then there’s fibre-optic weaving, which is where the whole thing starts to feel like a gaze.

We’re used to light arriving at textiles: spotlights, windows, screens. Fibre optics makes light come from within, as if the cloth has grown a circulatory system. The weave begins to glow not as an “effect,” but as a condition—light slipping along threads the way thought slips along synapses. When a viewer approaches, the glow can thicken, shift, or flicker. Not just “on/off” but a vocabulary: density, direction, tempo. It’s difficult not to read it as attention.

This is where the room changes. You realise the work isn’t merely illuminated. It’s aware. Or at least, it performs awareness convincingly enough to make your body behave as if it were true. You lower your voice. You slow down. You become careful, the way you do around animals whose intentions you don’t fully understand. People like to call this moment “Digital Craftsmanship,” as if the phrase could smooth out the friction. It tries to reconcile two histories: the slow intelligence of the hand and the quick intelligence of the circuit. Sometimes the reconciliation works. Sometimes it feels like a polite takeover. Because the hand has its own archive. Traditional textiles preserve labour in their imperfections: the slightly uneven tension, the stubborn knot, the tiny correction that remains visible because there was no time—or no desire—to erase it. That’s not just “texture.” That’s memory: of fatigue, of repetition, of skill earned and sometimes lost mid-process. It’s the human body leaving its signature in the only way it reliably can—through micro-failure.

Smart textiles risk replacing that kind of memory with a different one: frictionless, instantaneous, clean. When the cloth becomes too responsive, too fluent, too good at performing life, what gets edited out is the very thing we often come to textiles for—the evidence of time. Yet it would be lazy, even dishonest, to frame this as a simple death of craft. Some of the most forward-looking work on your site isn’t about sensors at all—it’s about the intelligence of material life cycles, and the moral weight of what we choose to keep forever.

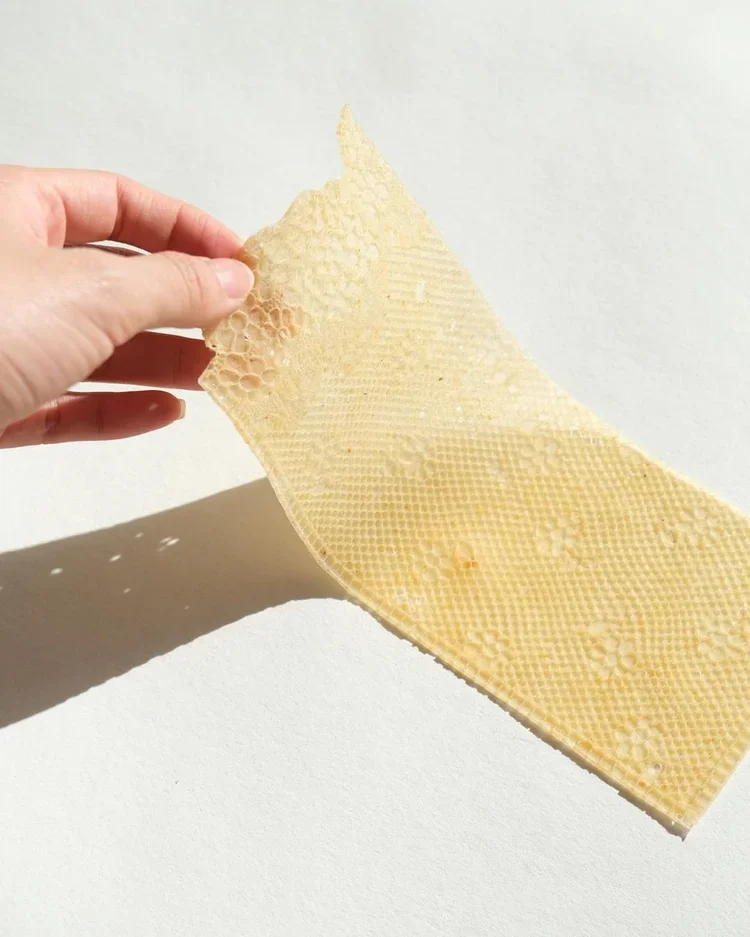

Zhixin Xue’s Milk leather—biomaterial derived from casein in expired milk—does something quietly radical: it grants the material a dignified exit. It insists that “value” can include biodegradation, that an object can be designed to leave no corpse behind. There is a kind of tenderness in that, a refusal of permanence as the default aesthetic.

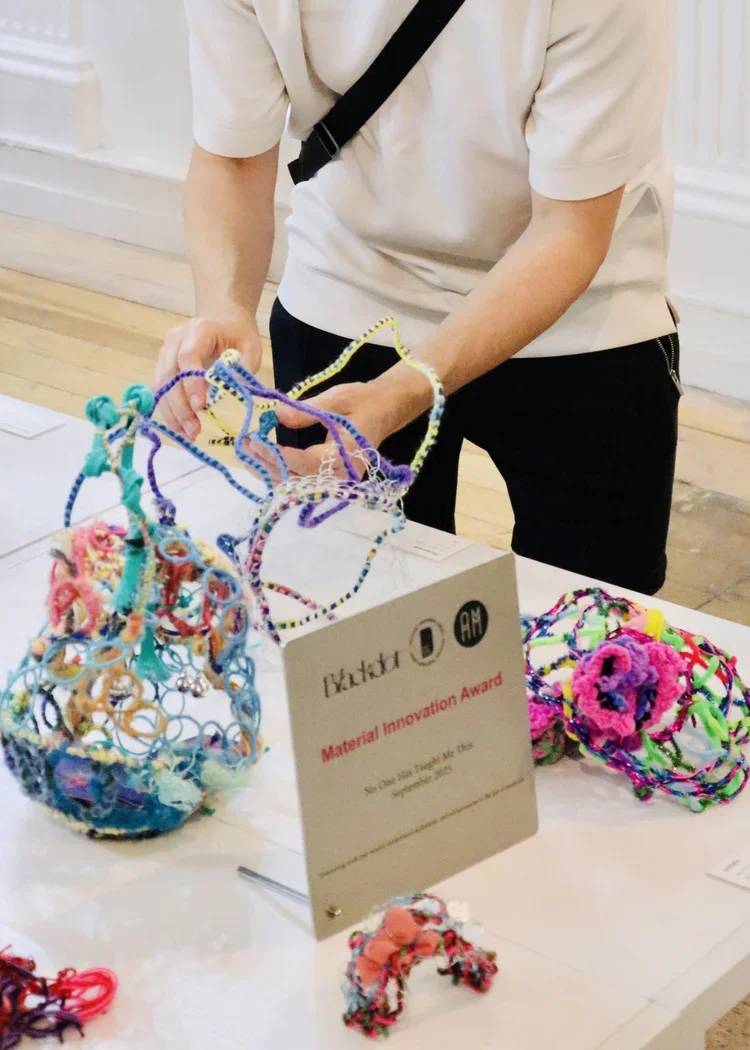

Pair that with Amy Hsu Tzu Chen’s Exploring the Soft Resilience Within, and the future stops looking like an electronics catalogue. Chen’s language is crochet, weaving, wrapping—techniques historically tied to domestic labor and the gendered politics of “softness.” But she interrupts softness with tension: wire, metallic twists, pipe cleaners—materials that bend, yes, but only by holding strain inside themselves. The work asks your hand to participate. It reminds you that responsiveness can come from structure and discipline, not only from computation.

All of this circles back to the question we keep trying not to ask out loud: when textiles start sensing, who is sensing whom?

There’s a seductive narrative that smart garments and perceptive tapestries are simply extensions of the human body—extra skin, extra intuition, a gentle upgrade. The phrase “posthuman sensing” often arrives dressed as liberation: expanded perception, distributed intelligence, a softer relationship between organism and environment. But textiles have always been intimate technologies. They sit against sweat. They memorise the curve of your shoulder. They know how you move before anyone else does. When you add sensing, you add legibility. And legibility is never neutral.

Because the same cloth that tightens to warm you can also tighten to guide you. The same fibre that registers your touch can also record your stress. The same glow that seems to comfort can also signal. Once emotion becomes measurable, it becomes governable. Once the body’s small fluctuations are captured, they can be modeled—and once modeled, they can be used.

Picture it late at night on the Underground. You’re wearing a jacket threaded with SMA and conductive fibres. A gust hits the platform; the collar pulls itself closer to your neck. You feel safer. Your heart rate lifts anyway—an older animal fear, the kind no amount of modern lighting really erases. The cuff responds: a faint ring of fibre-optic light appears, soft as a pulse, as if the garment is saying, I’m here.

And maybe it is.

Or maybe it’s saying something else—something you can’t hear.

Not to you, but about you.

If fabric can learn your body this well, the question isn’t whether textiles will become more “alive.” The question is: when the cloth starts keeping count of your sensations, who gets to read the tally—and what do they do with it?

Responsible Editor

Isabel Pavone